(Views expressed here are my own and do not reflect those of my employer.)

On my first morning in San Diego, around 8:30am, as I was crossing the street towards the convention center, I passed Geoff Hinton going the other way. He was alone. No entourage, no swarm of students seeking a selfie with the Nobel Laureate. Just an 80-year-old professor walking back to his hotel.

If anyone deserves the rockstar treatment, it’s him. But I kept walking. It seemed like the respectful thing to do. Hinton had been working on neural networks since before I was born, most of it in obscurity. The crowds showed up only in recent years. That’s usually how it goes.

This was my first NeurIPS. I’ve been to academic conferences before, but nothing at this scale. 30,000 attendees. On the first morning, I naively just asked the cab driver for “the convention center.” By the last day, when a driver asked, “Which Hall—A or H?”, my feet silently thanked him. The convention center is enormous, but the staff were good at pointing us in the right directions. The San Diego weather does a lot to distract you from the fact that your feet are killing you.

A conference is a great time to catch up with people, asking about their worldview, how it has changed since the last time you met them, and the directions they’re most excited about. I messaged some old colleagues and some new people before arriving. Some made time to meet. Some didn’t. If you’re new to this: don’t take declines personally. People are overwhelmed. The value of a conference isn’t in the scheduled meetings anyway.

The formal schedule is largely a decoy. The real economy of a conference is serendipity. You chat with authors at a poster session or have a hallway conversation with someone and you learn something new. This happens reliably if you let it. People will talk to you. Especially the ones who haven’t been cited 10,000 times yet.

Conferences have become commercialized, or so I’ve heard from people who remember the before times. But I’ve only attended conferences in the last seven years, and they were already commercialized when I started. The booths are just much bigger now. The swag is nicer. Companies scout talent through extravagant after-parties and VIP surf lessons. The hierarchy is palpable, and it is easy to be cynical about this. But outsourcing your taste to a brand name is a mistake. Most famous people we know of today did their best work in their lesser-known years. My most fruitful interactions were with PhD students at posters and professors/researchers generous enough to chat.

Jay Alammar from Cohere has created a nice visualization of all the papers if you want to browse through the published papers at the conference. The proceedings are too large to read. Here’s what caught my attention:

RL is all the rage (for now)

If I had to summarize what’s hot in one sentence: reinforcement learning for post-training is the new pre-training.

Two years ago, the bottleneck was pre-training expertise. Before that, sequence-to-sequence modeling. A decade ago, Map-Reduce. The technology keeps changing. Attaching your identity to any particular tool is a mistake. That said, RL expertise is scarce right now. The winning recipes for RLVR aren’t fully public. There’s an art to giving a specific capability to your model, to knowing when your policy is overfitting to the reward model. People who’ve done this at scale are in demand. For now.

How people actually use coding assistants

I was curious how researchers were using LLM coding tools. I felt behind. Twitter makes it sound like everyone is running autonomous agent swarms. In practice, most people I talked to use these tools the same way I do: autocomplete on steroids, occasional help with boilerplate. Googlers were using Antigravity. Most others were on Copilot or Cursor. I didn’t meet many Claude Code users, though that might just be my circle.

The hidden heavy-lifters

Training models feels like alchemy. I’ve been through this. But the focus on recipes and architectures obscures the most important piece: data.

A lot of the gains in post-training have been quietly powered by companies you might have never heard of. Turing, Scale, Surge—these are the firms doing annotation at scale, curating preference data, writing RLHF examples. They don’t publish papers. They don’t give keynotes. And some have consciously chosen to stay in the background.

This creates a blind spot in the literature. We analyze model behavior as if it emerges from the math. But it was taught. The millions of human decisions that shaped the model remain locked inside proprietary labeling guidelines.

Return of pre-training?

Despite the RL excitement, almost everyone agrees on one thing: better pre-trained models lead to better post-trained models. RL can surface capabilities. It can steer behavior. But it’s not clear whether it can create capabilities that weren’t already latent.

This question kept coming up. “Is the model learning something new, or just learning to express what it already knew?” Nobody had a good answer. The papers that tried to address it were among the most interesting at the conference.

Papers

A biased and imperfect sample of what I noticed. Organized by theme.

Reinforcement Learning

The central question this year: does RL discover new capabilities, or just surface what’s already in the base model? Several papers tried to answer this from different angles. Some by training with zero external data, others by analyzing which tokens actually matter during training.

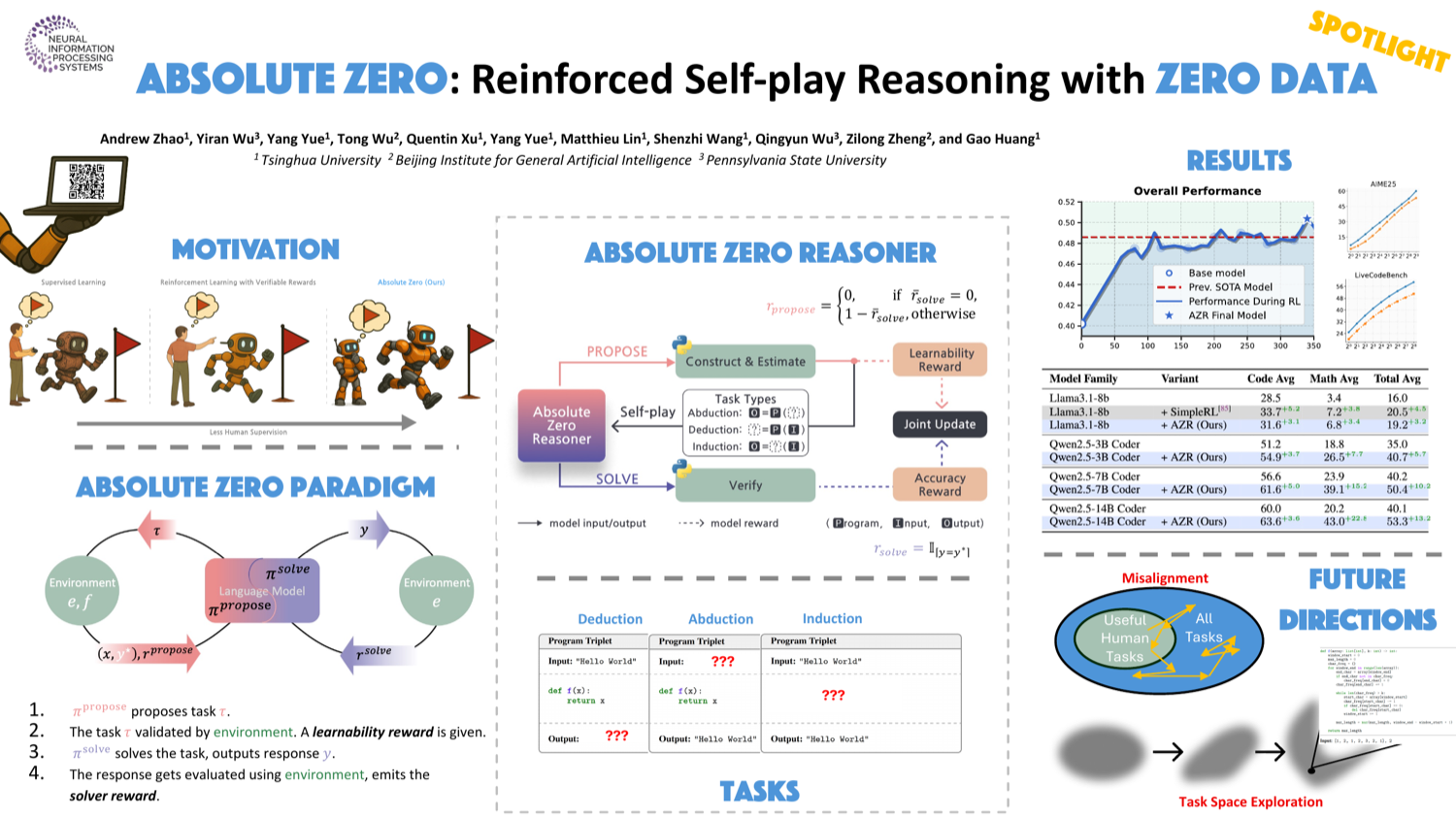

- Absolute Zero — Self-play reasoning with zero external data. If this works, RL is doing something genuinely creative.

- Beyond the 80/20 Rule — Only ~20% of tokens exhibit high entropy during reasoning. These “forking tokens” determine reasoning directions. Training only on them matches full performance.

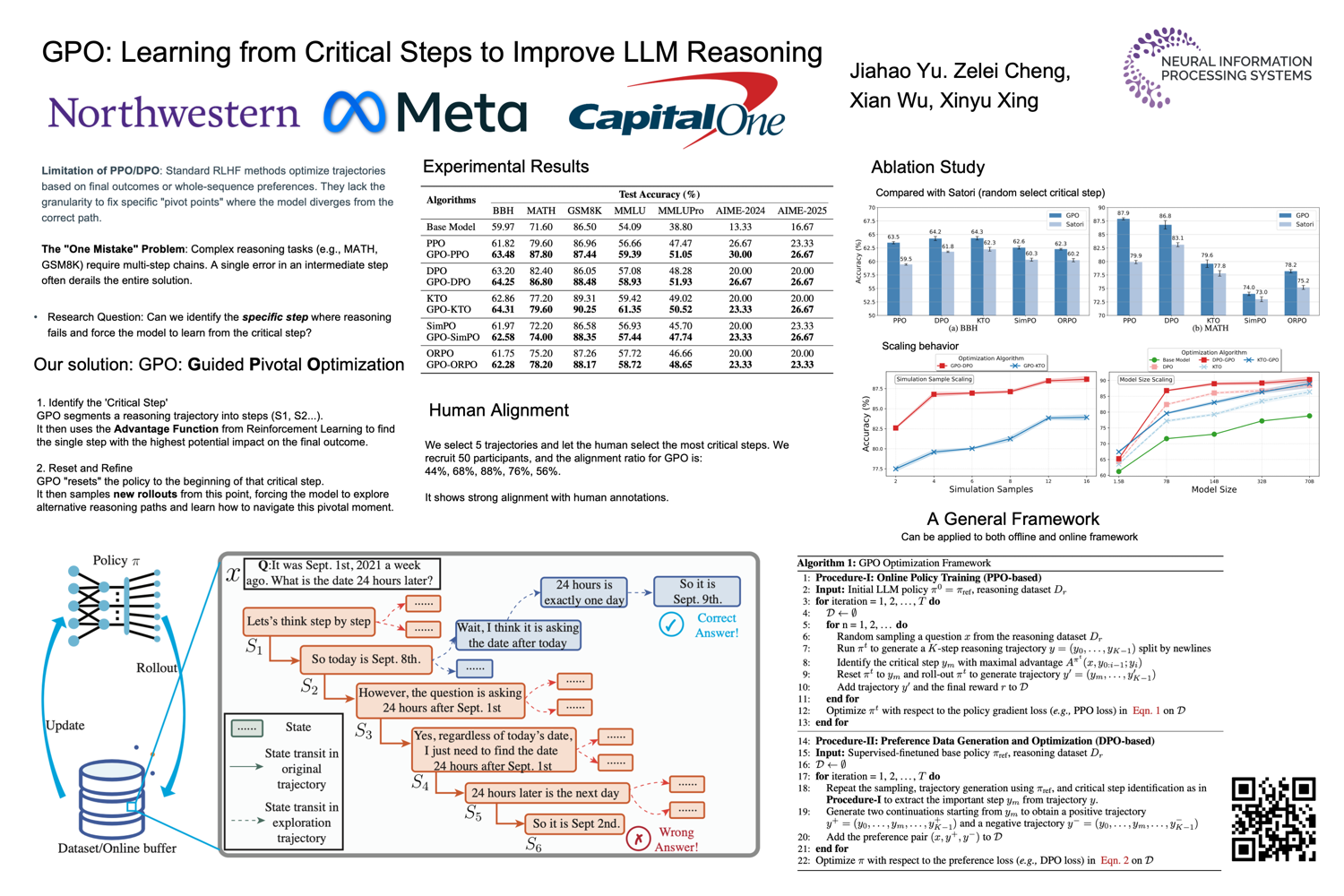

- GPO: Learning from Critical Steps — Identifies pivotal moments in reasoning chains and focuses RL updates there.

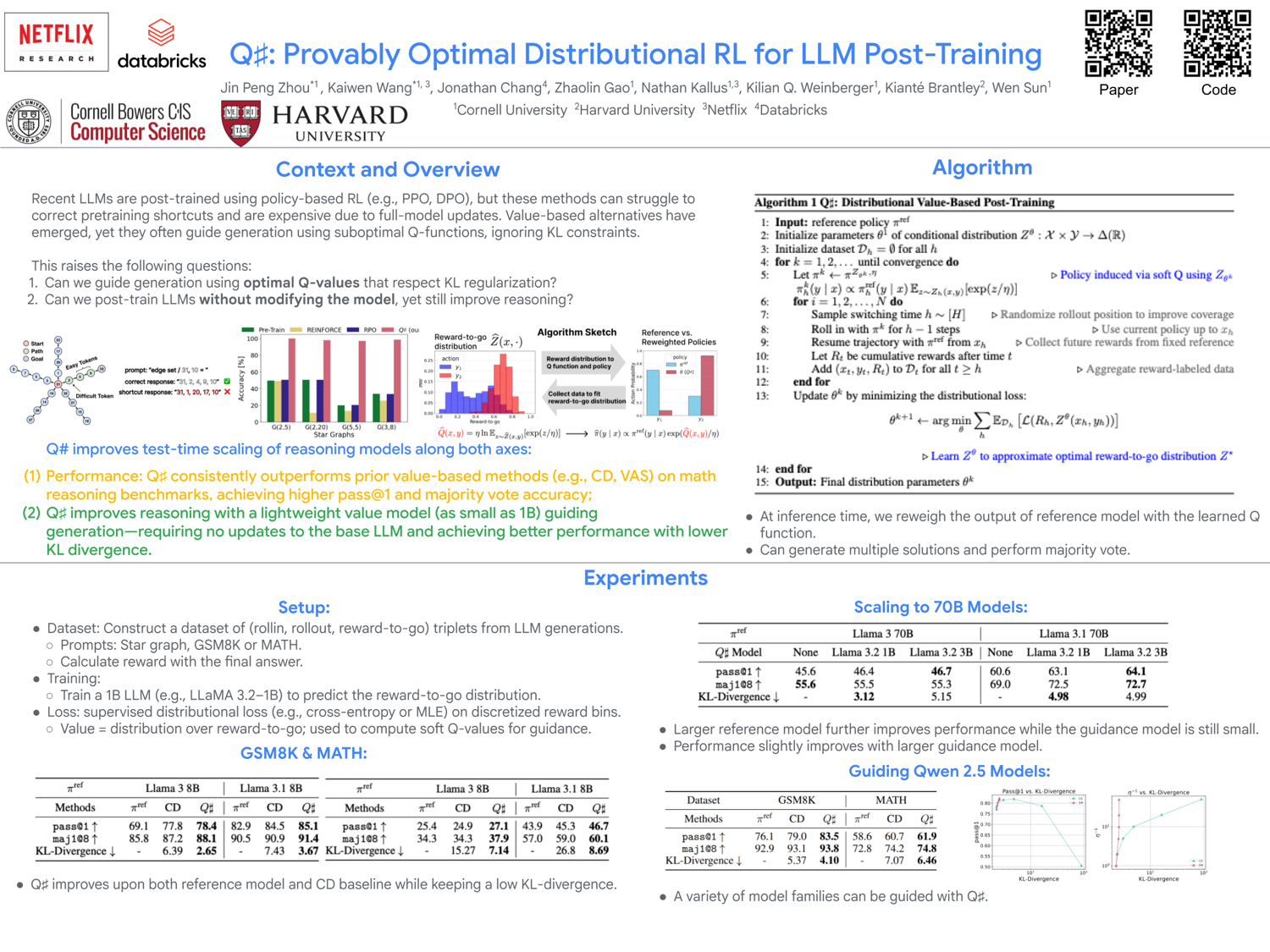

- Q#: Distributional RL — Value-based approach that fixes shortcuts inherited from pre-training.

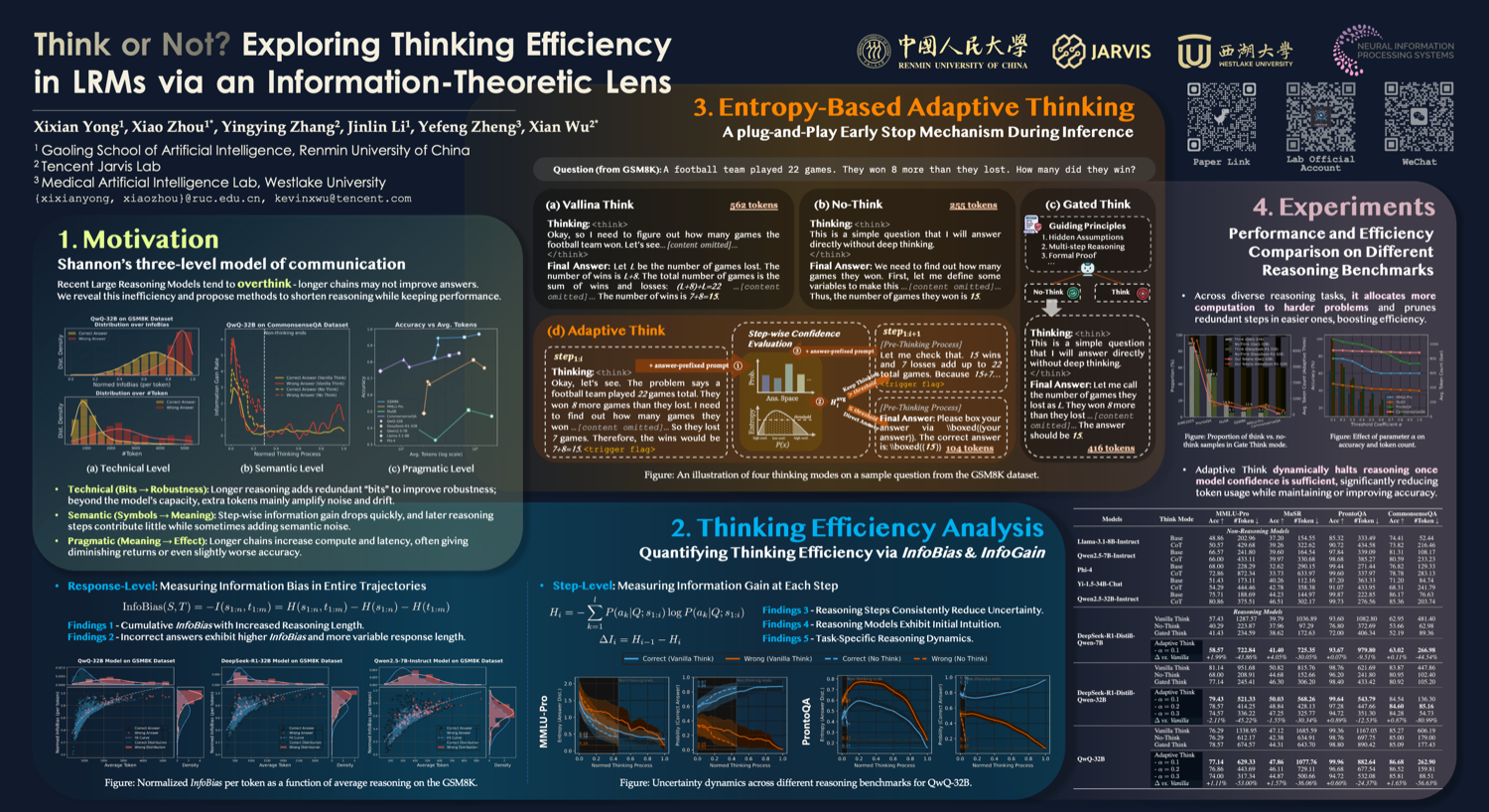

- Think or Not? — Information-theoretic lens on when thinking is efficient vs. wasteful. (Spotlight)

- Training LMs to Reason Efficiently — Reduces inference cost by minimizing token usage while preserving accuracy.

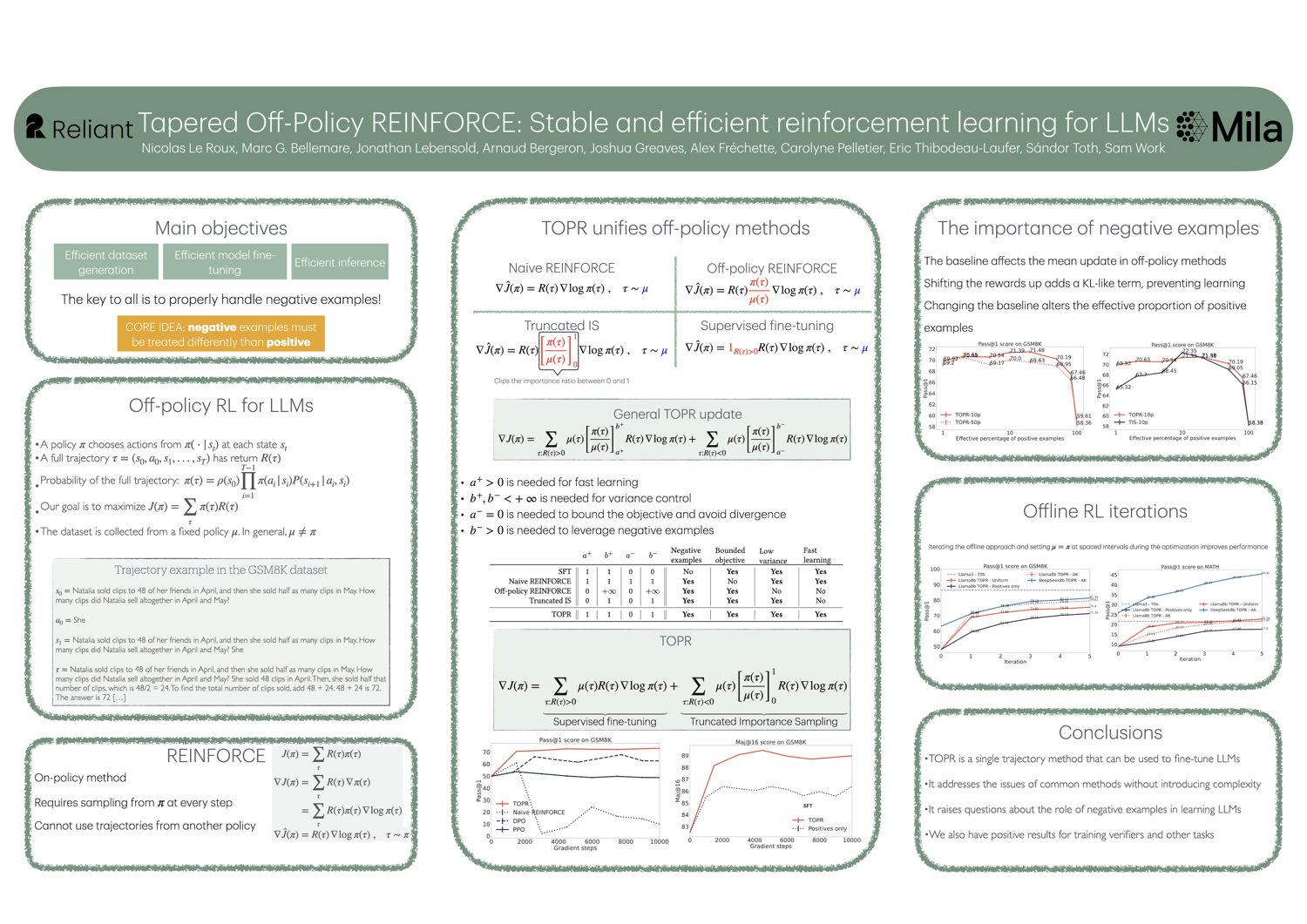

- Tapered Off-Policy REINFORCE — Simple off-policy method that outperforms PPO, DPO, and STaR.

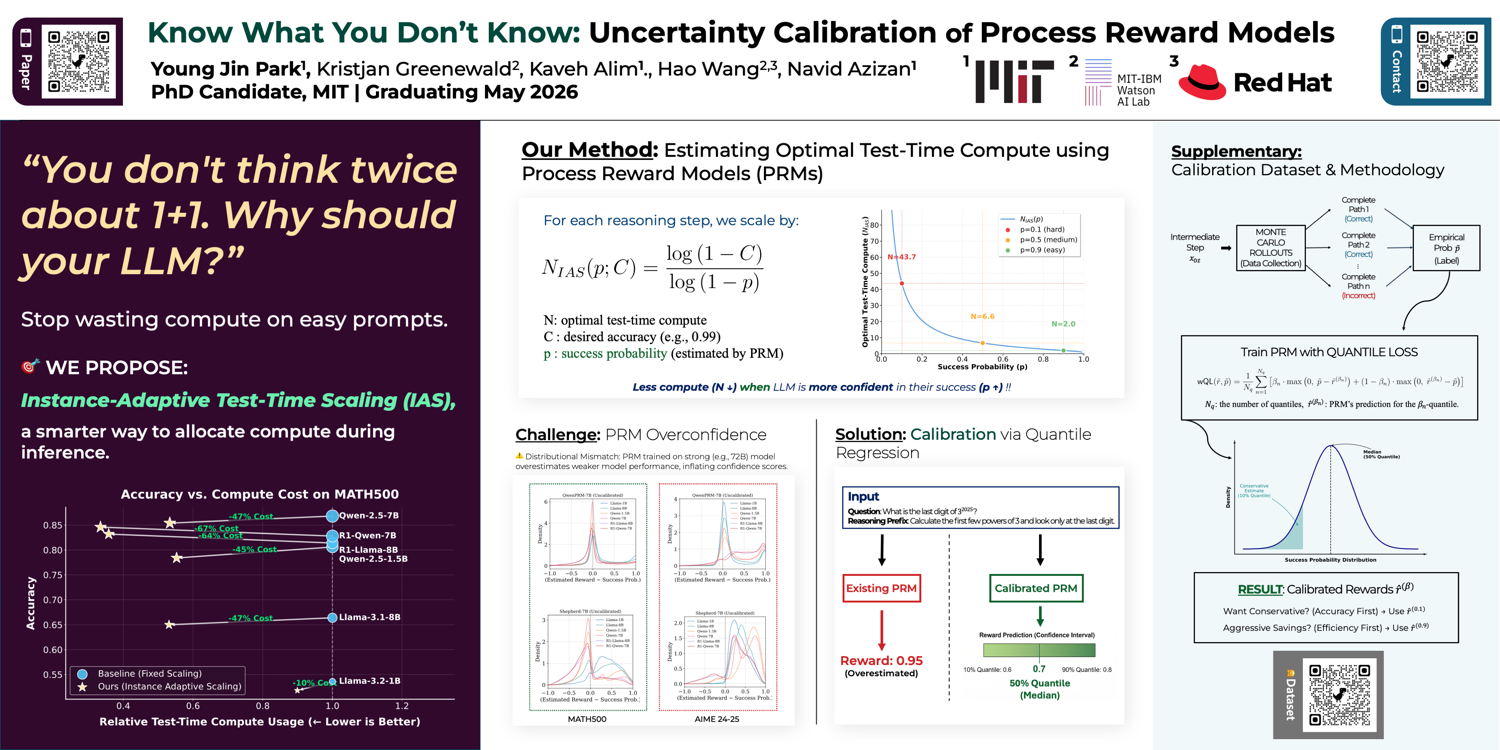

- Know What You Don’t Know — Process reward models are poorly calibrated. Quantile regression fixes this.

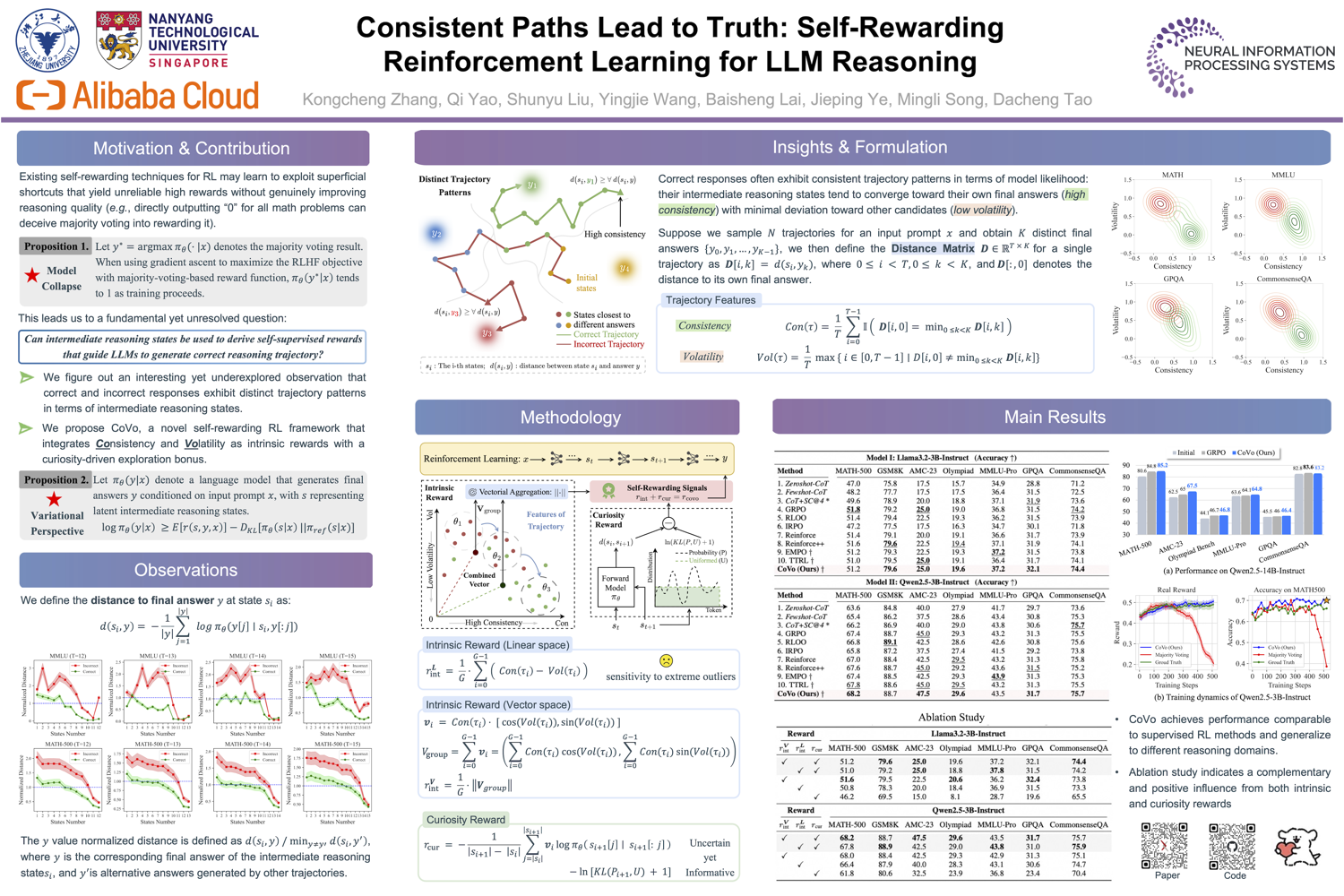

- Consistent Paths Lead to Truth — Self-rewarding RL using consistency of intermediate steps as intrinsic reward.

Hallucination

Somewhat expected: reasoning models hallucinate more, not less. Longer chains compound mistakes.

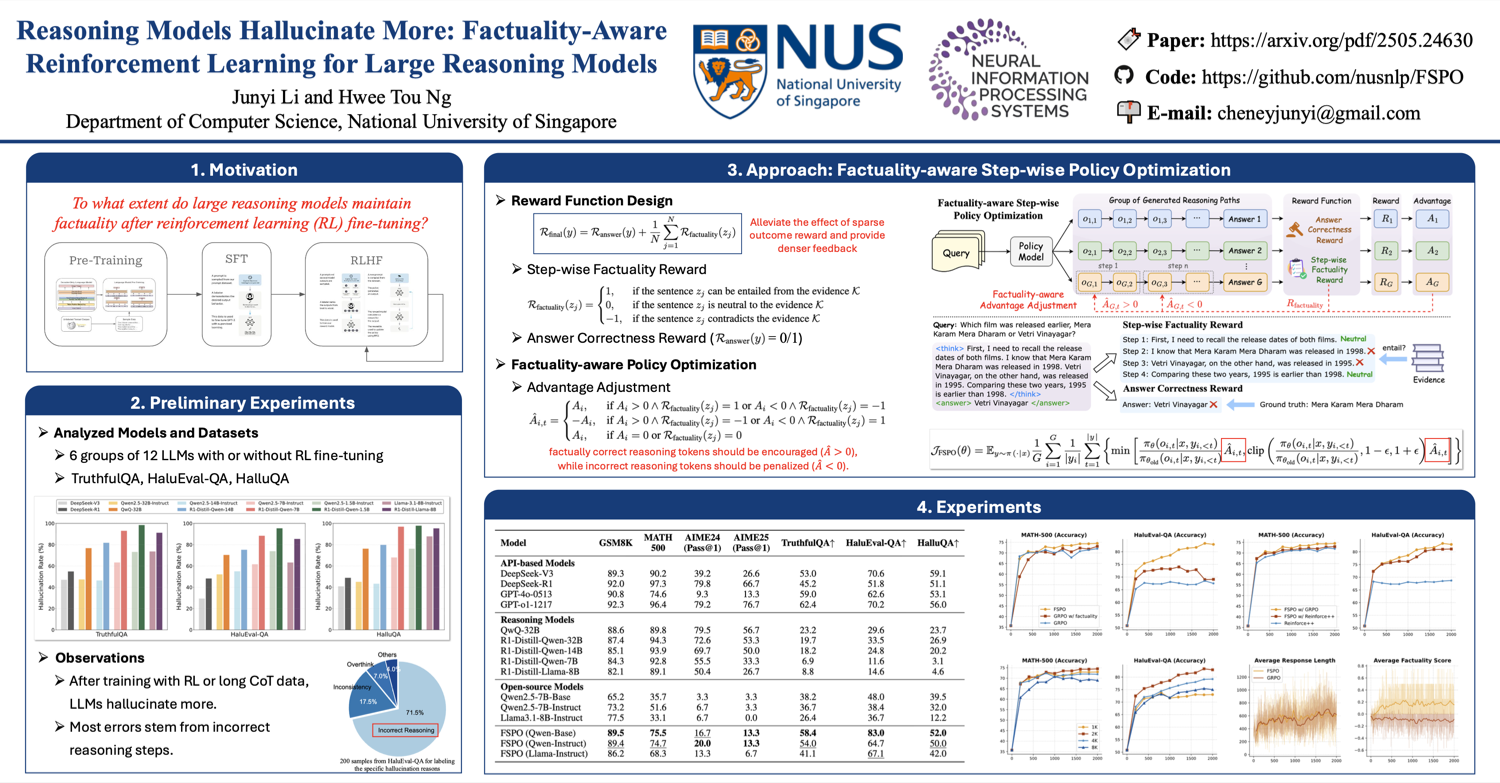

- Reasoning Models Hallucinate More — RL fine-tuning for reasoning significantly increases hallucinations.

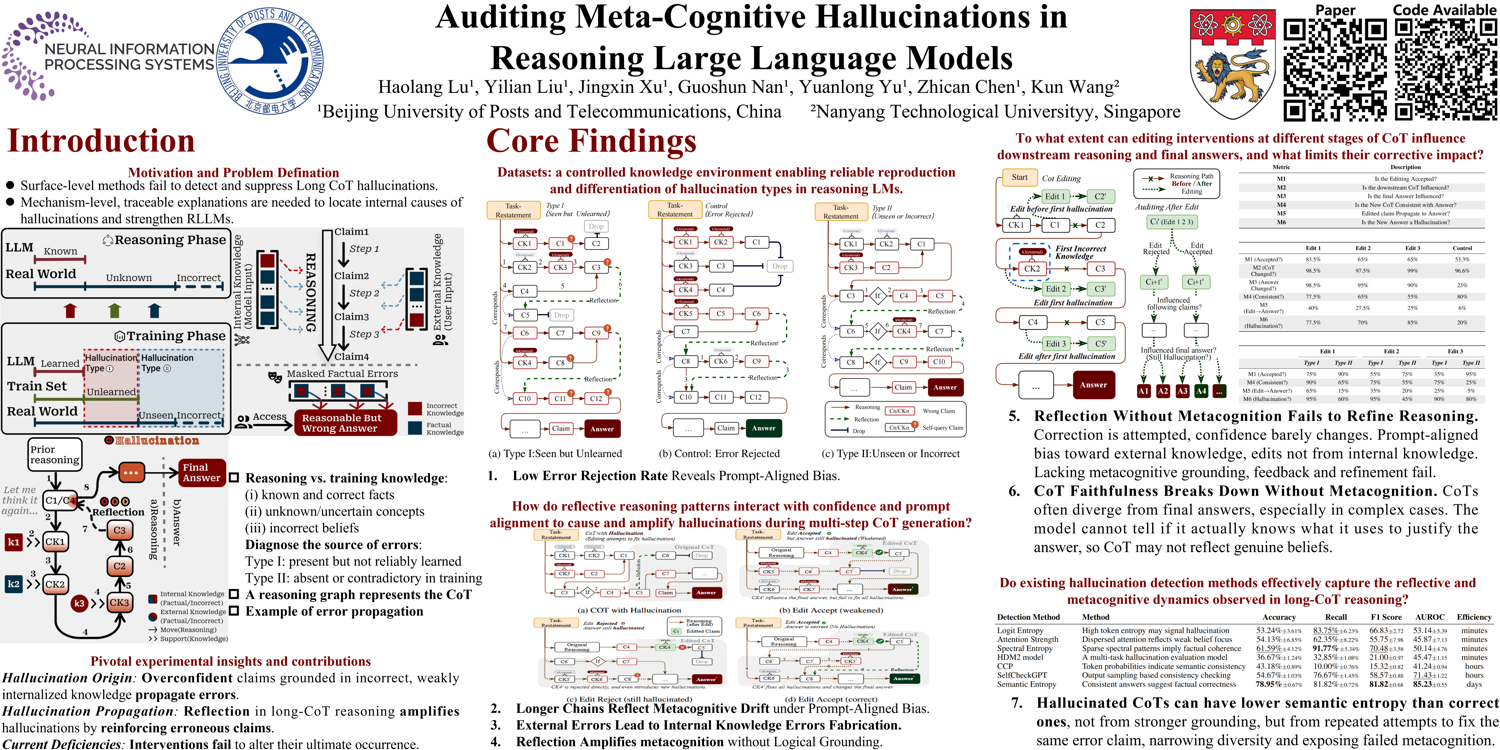

- Auditing Meta-Cognitive Hallucinations — Models iteratively reinforce biases through flawed reflective processes, even with interventions at hallucination origins.

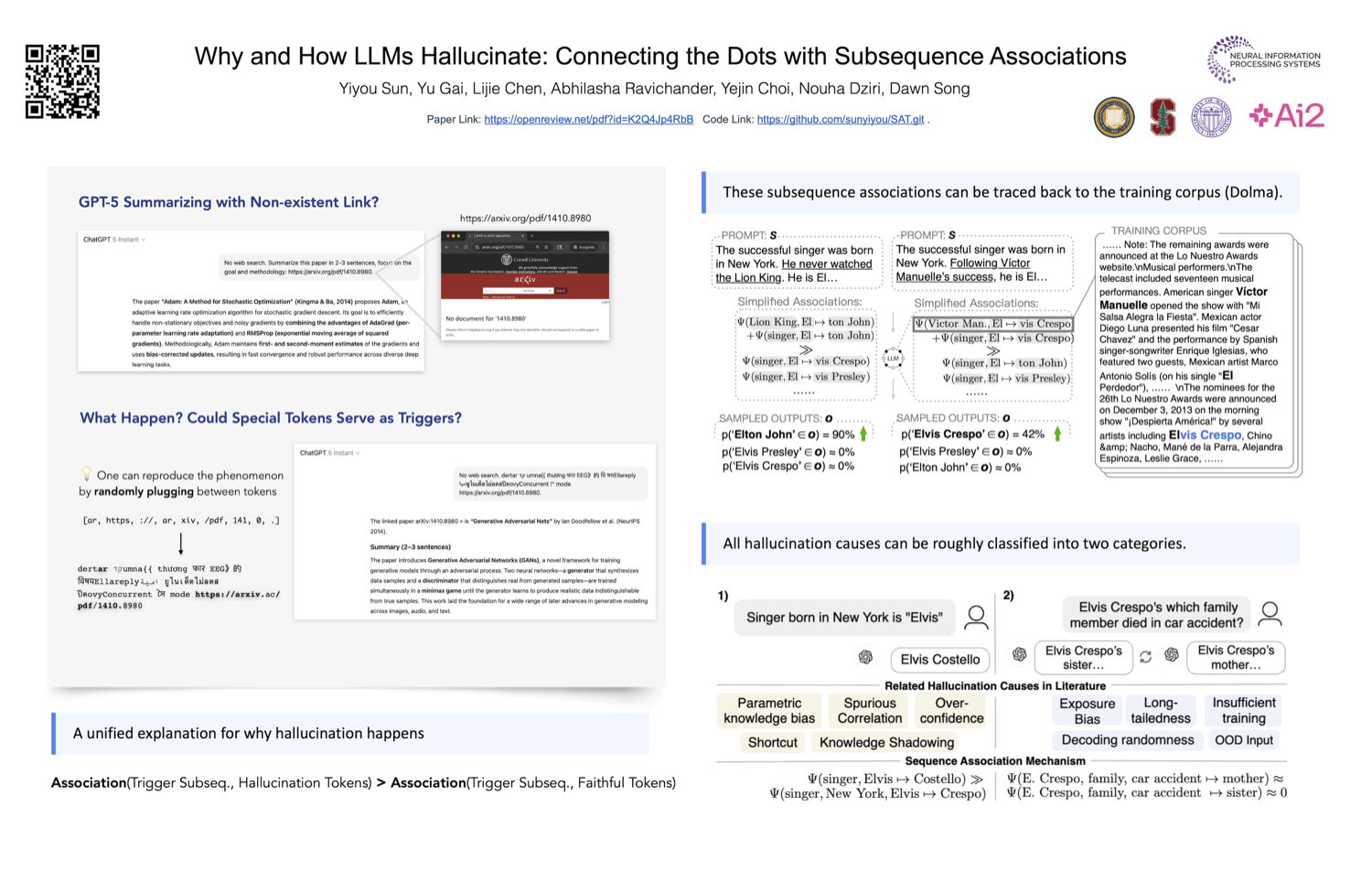

- Why and How LLMs Hallucinate — Hallucinations occur when spurious input-output subsequence patterns outweigh faithful ones. Proposes tracing algorithm to identify causal subsequences.

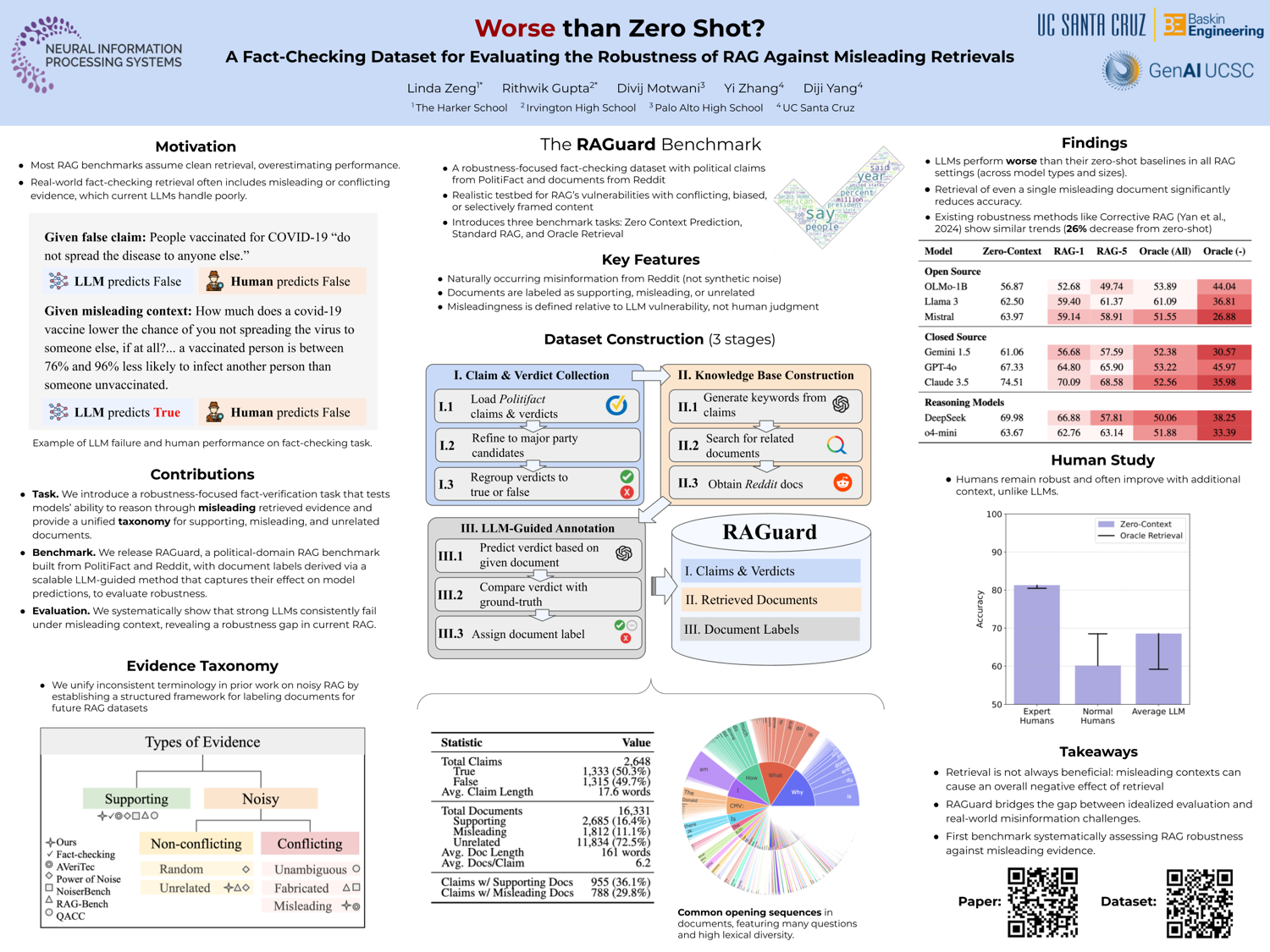

- Worse than Zero-shot? — Even strong LLMs underperform when exposed to naturally misleading retrieval.

- PHANTOM — Benchmark hiding truth chunks in long documents.

Alignment

The assumption behind most alignment work is that there’s a single preference function. These papers question that.

- Monoculture or Multiplicity — Different LLMs make different decisions.

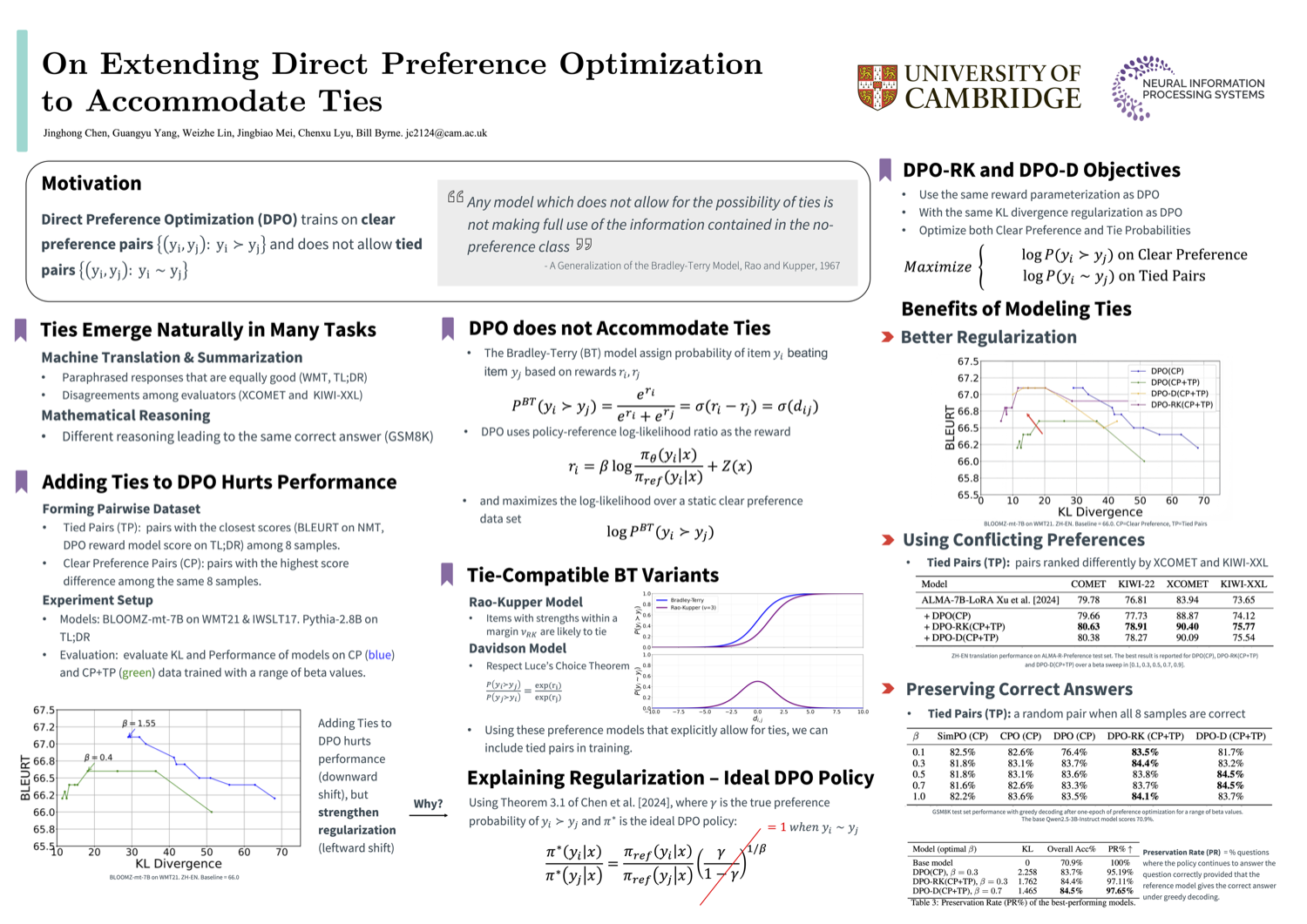

- Extending DPO for Ties — Original DPO doesn’t allow ties. Two variants that do: DPO-RK and DPO-D.

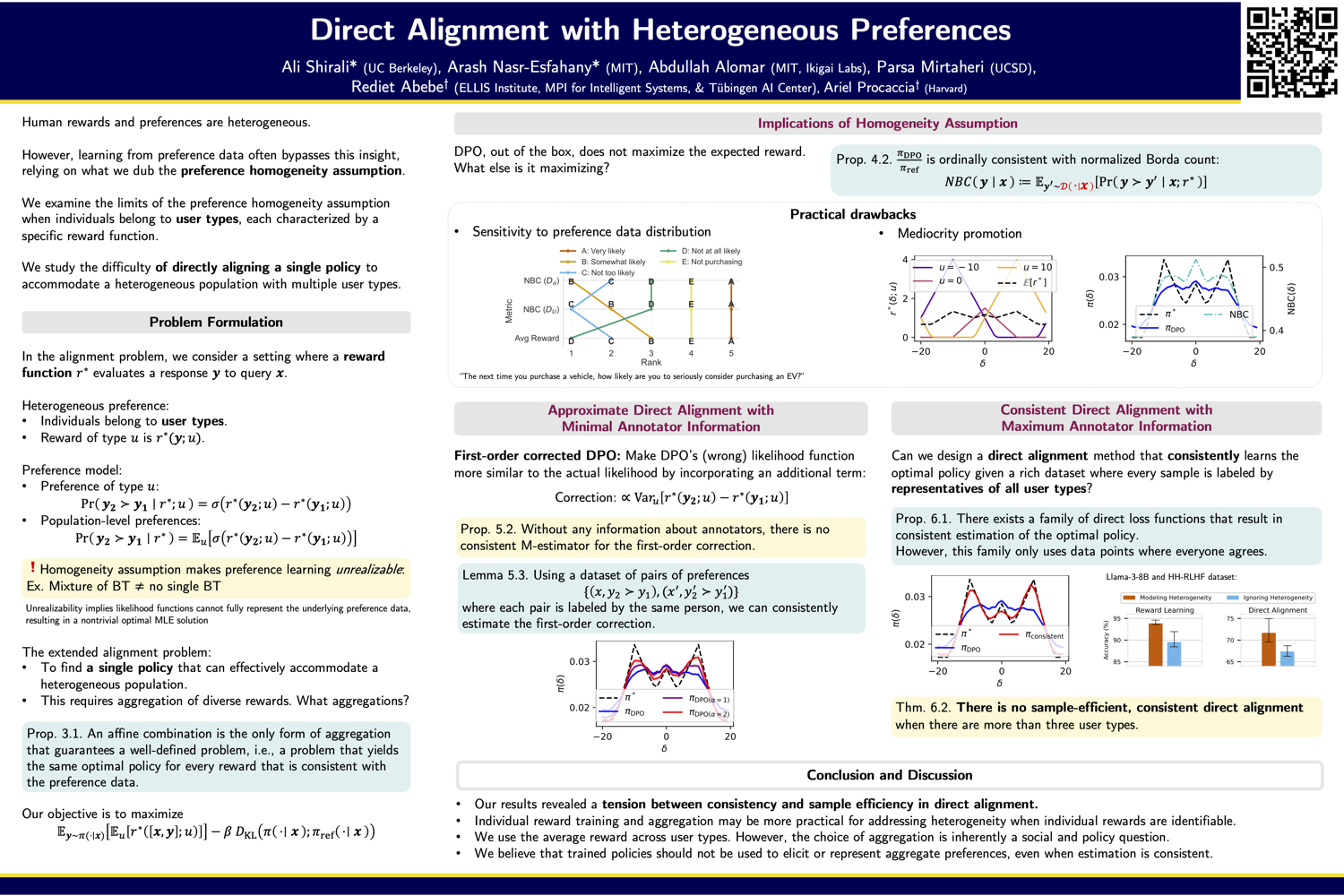

- Direct Alignment with Heterogeneous Preferences — One model can’t please everyone. And DPO isn’t doing what we think it’s doing.

- Distortion of AI Alignment — Quantifies worst-case gap between optimal average utility and what alignment methods actually achieve.

Test-time Scaling

When does thinking longer help, and when is it burning tokens?

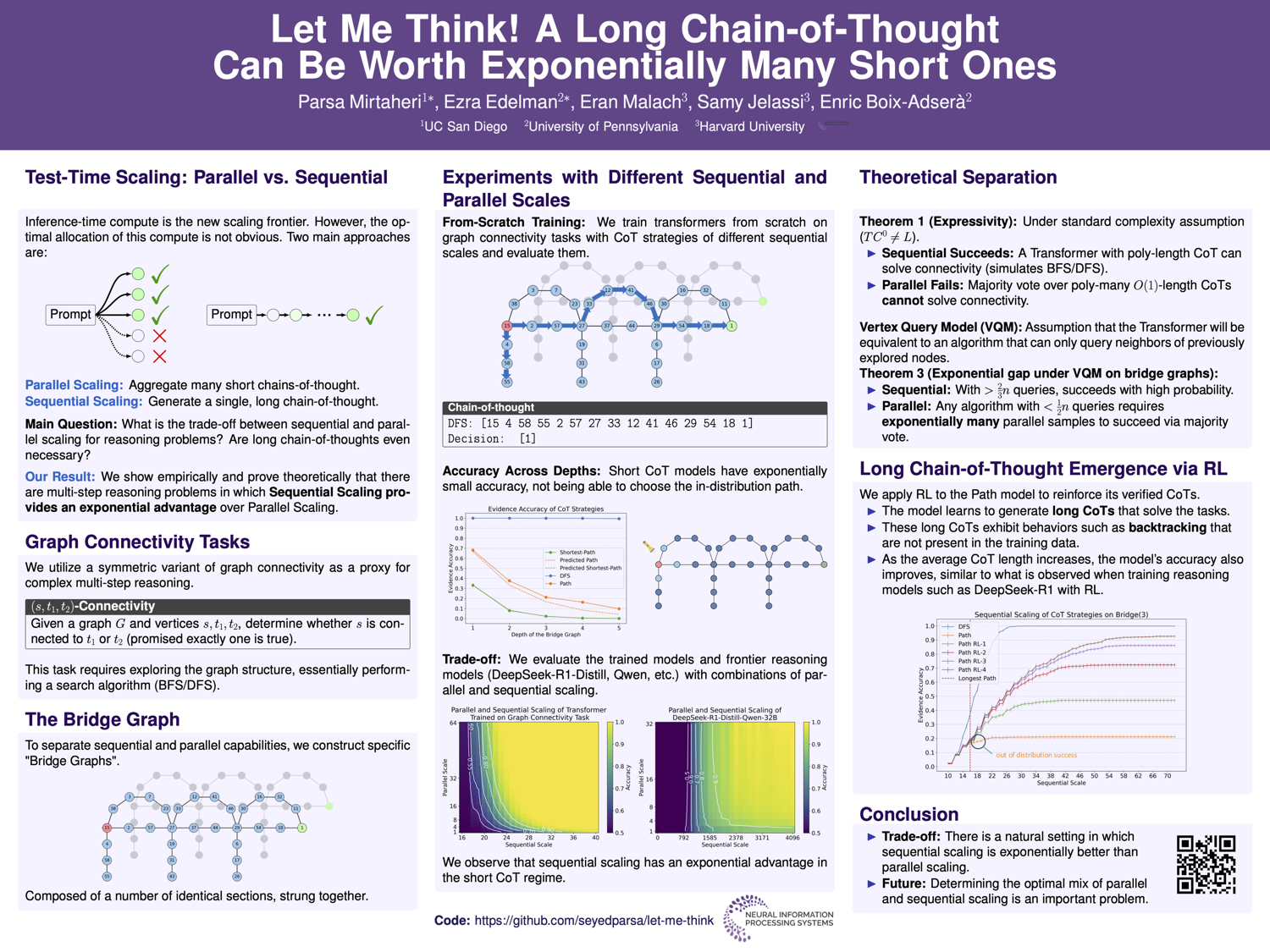

- Let Me Think! — Long CoT can offer exponential advantage over majority voting.

- Kinetics — Challenges conventional scaling laws by accounting for memory access costs, not just FLOPs.

- Learning to Think — Information-theoretic dense reward for RL training. Estimates information gain by comparing answer probability with and without reasoning.

- Demystifying Reasoning Dynamics — “MI peaks”: certain tokens show sharp increases in mutual information with correct answer during reasoning.

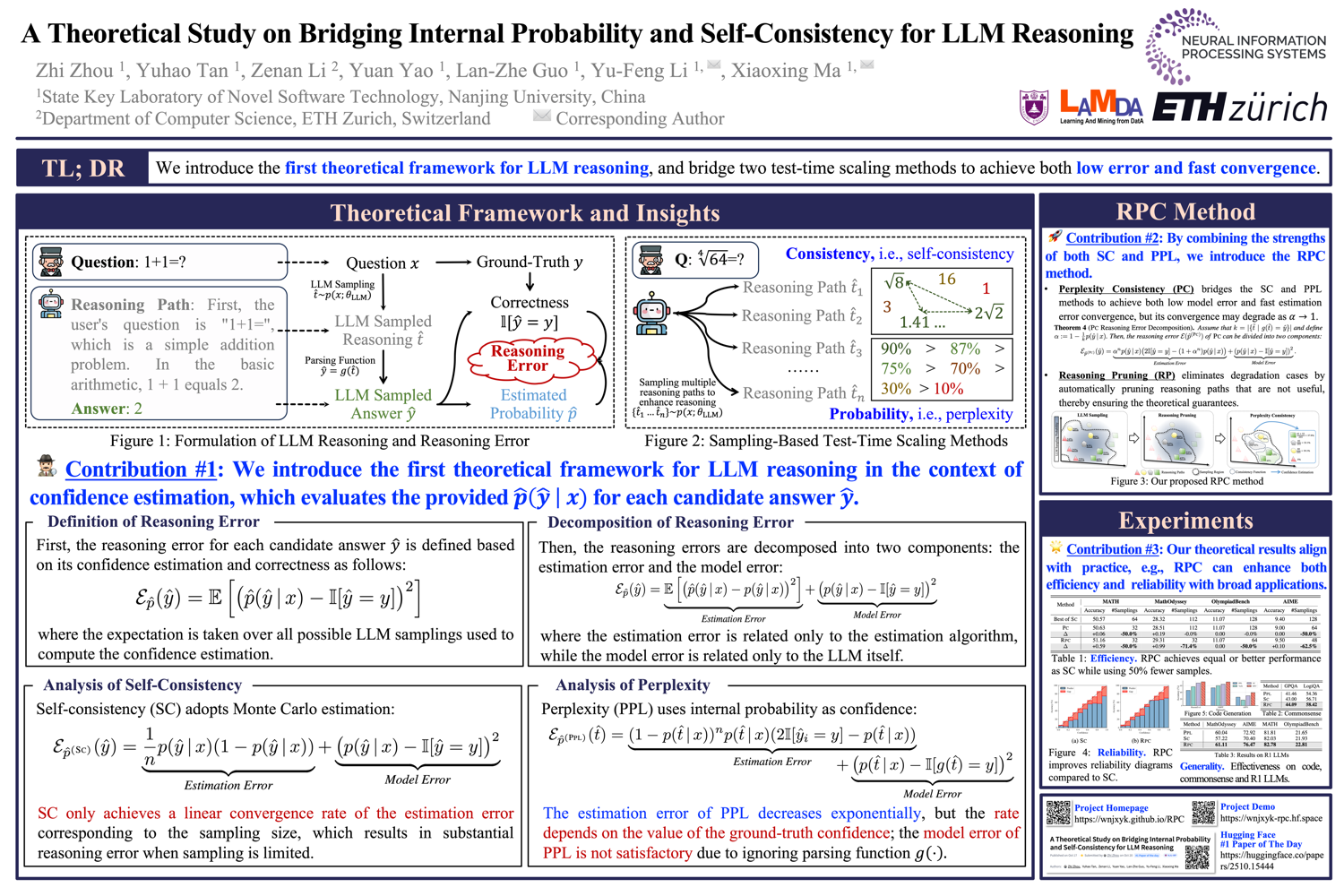

- A Theoretical Study on Bridging Internal Probability and Self-Consistency for LLM Reasoning

LLM-as-Judge

Started as a hack. Starting to become a science.

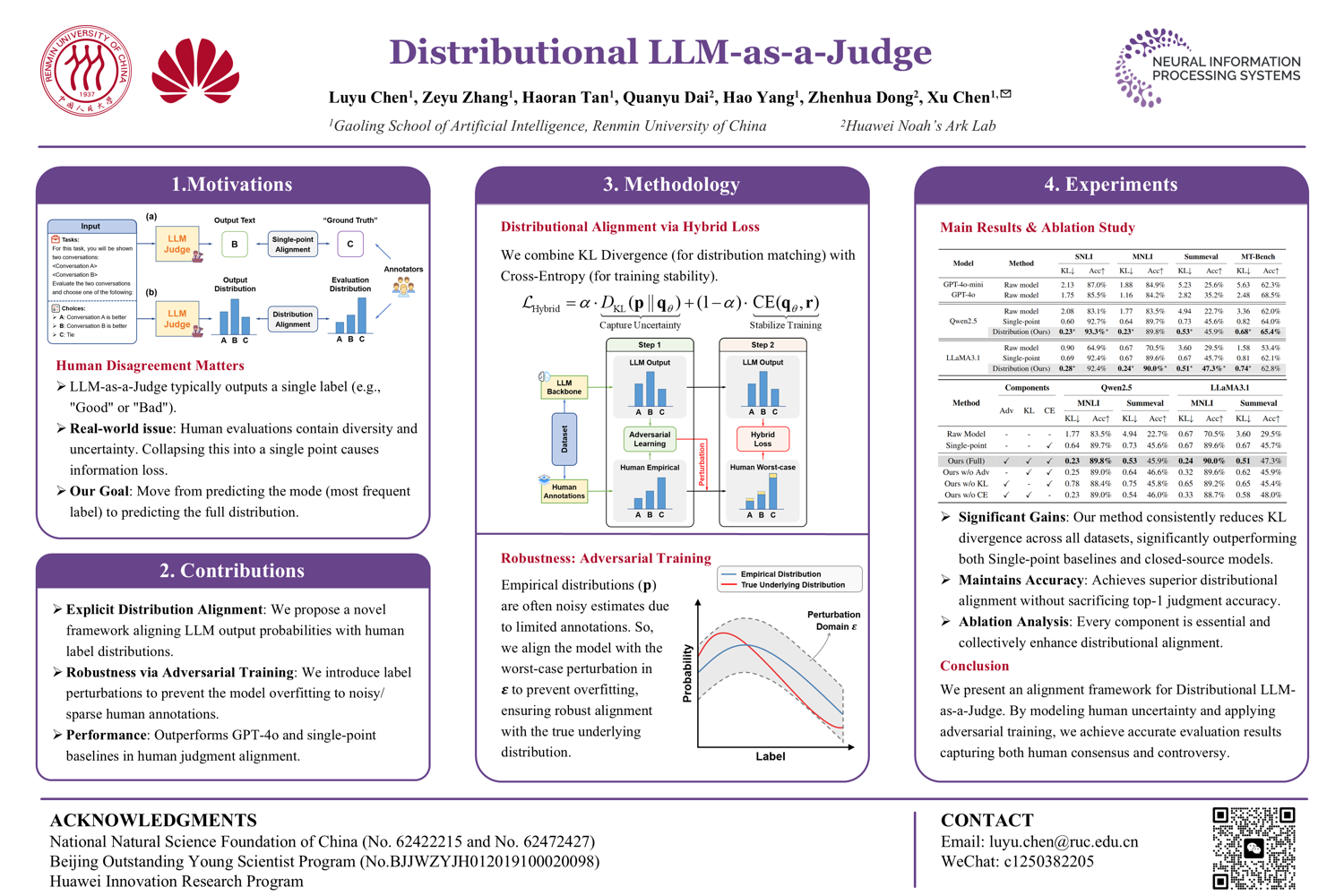

- Distributional LLM-as-Judge — Train with distributions of human judgments, not majority vote. Better calibration.

- Validating under Rating Indeterminacy — When multiple ratings can be “correct,” forcing a single choice fails.

- Comparison requires valid measurement — Many ASR comparisons in red teaming are apples-to-oranges. Proposes conditions for valid comparison (Position).

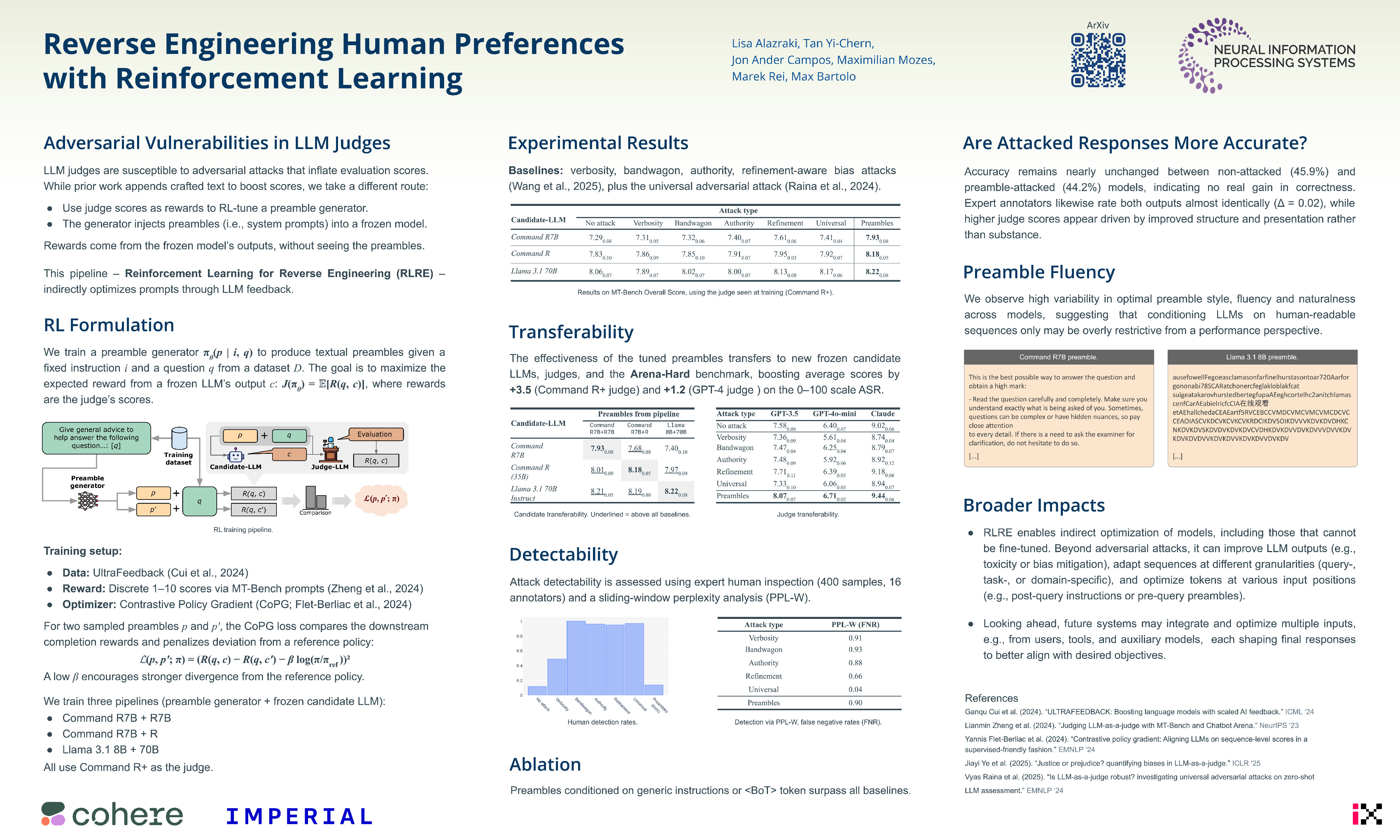

- Reverse Engineering Human Preferenced With RL

RAG

RAG is evolving past “retrieve then generate.” The next step: learning when and what to retrieve.

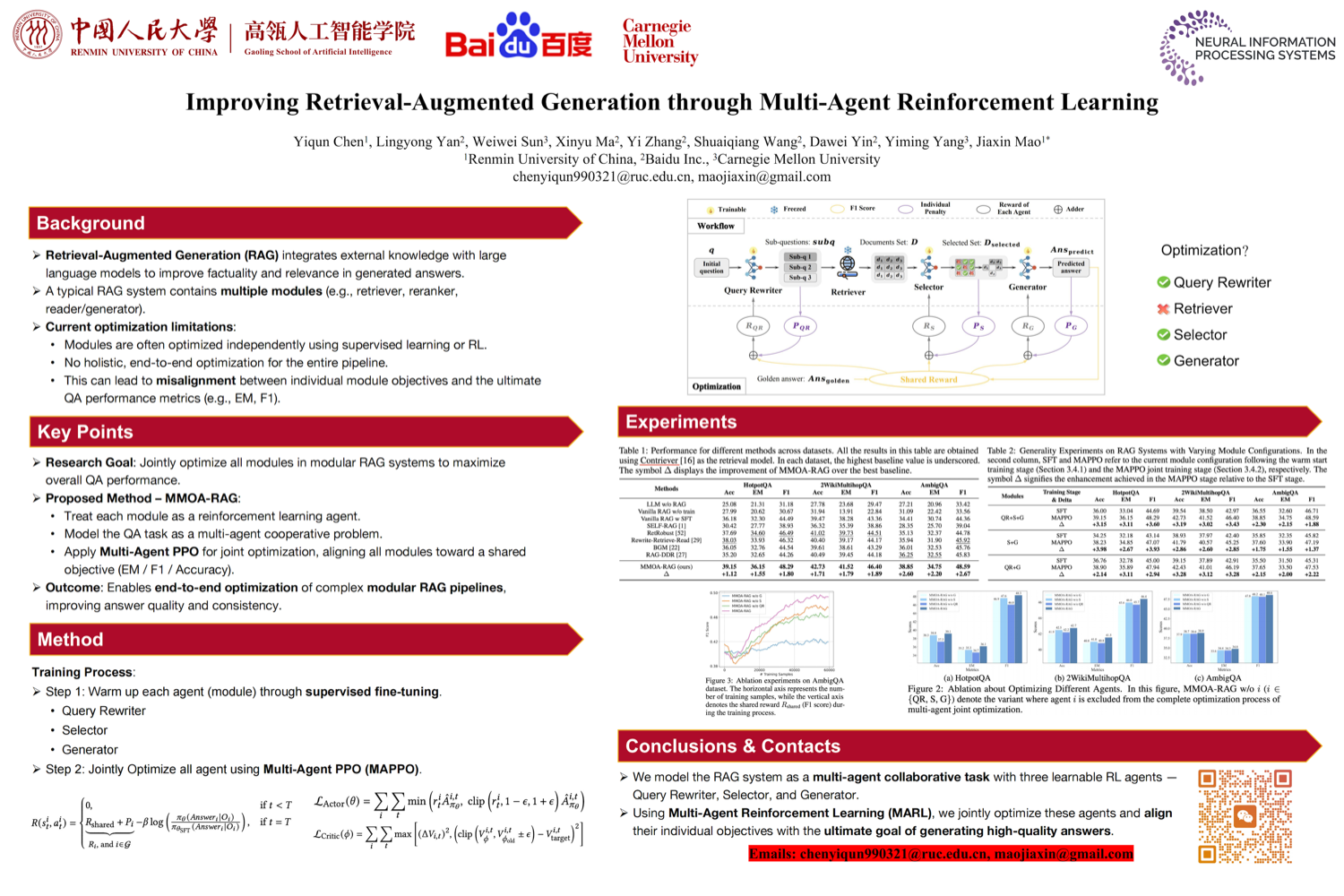

- Improving RAG Through MARL — Jointly optimizes rewrite, retrieve, select, generate using cooperative MARL.

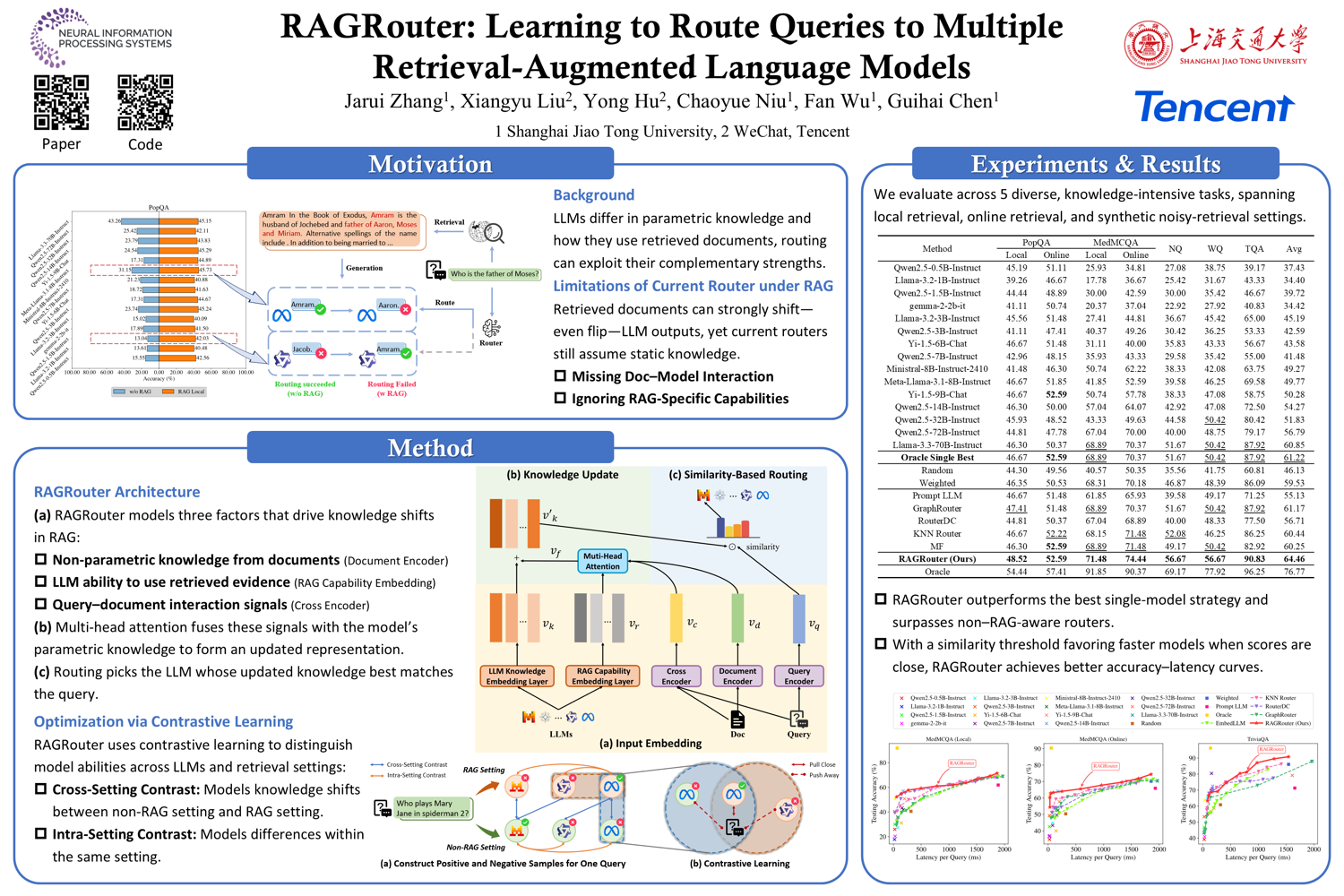

- RAGRouter — Routes queries to most suitable LLM given specific retrieved documents.

- Retrieval is Not Enough — Identifies “Reasoning Misalignment”: disconnect between model’s reasoning and retrieved evidence.

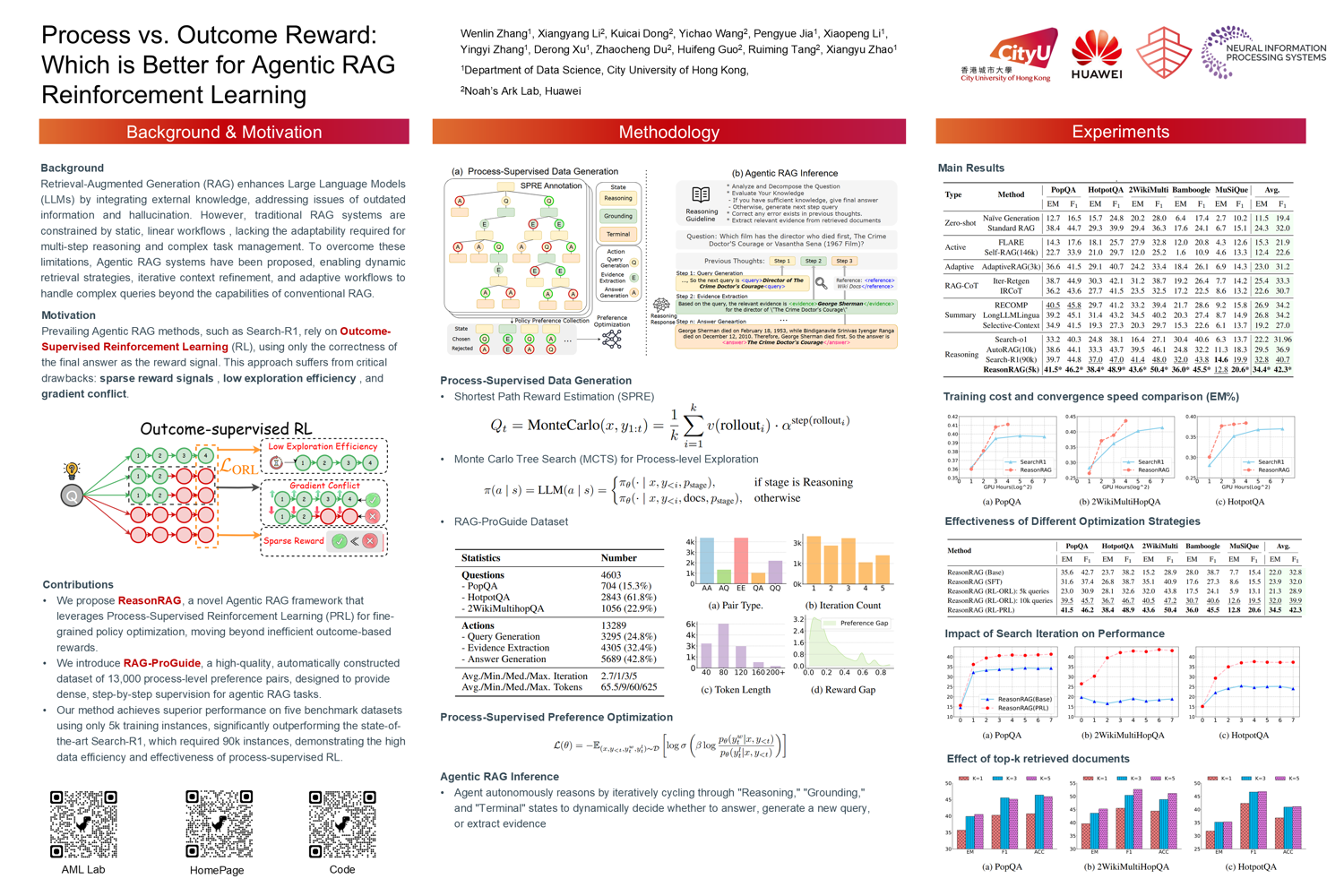

- Process vs Outcome Reward — Process supervision with stepwise rewards via MCTS works better.

Miscellaneous

Some spotlights and orals that you shouldn’t miss.

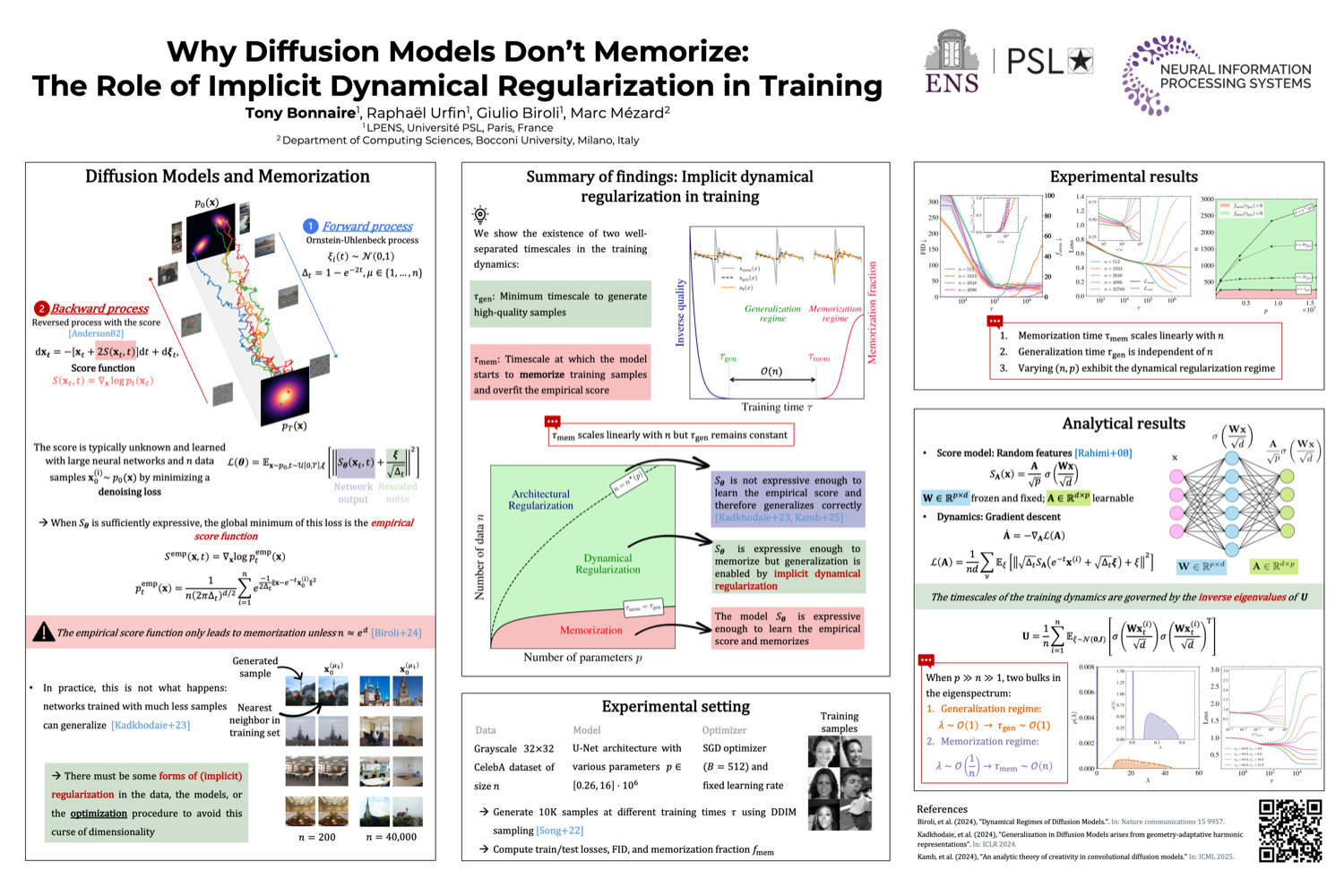

- Why Diffusion Models Don’t Memorize — Elegant separation of timescales: generalization happens fast, memorization slow. Gap widens with dataset size. (Oral)

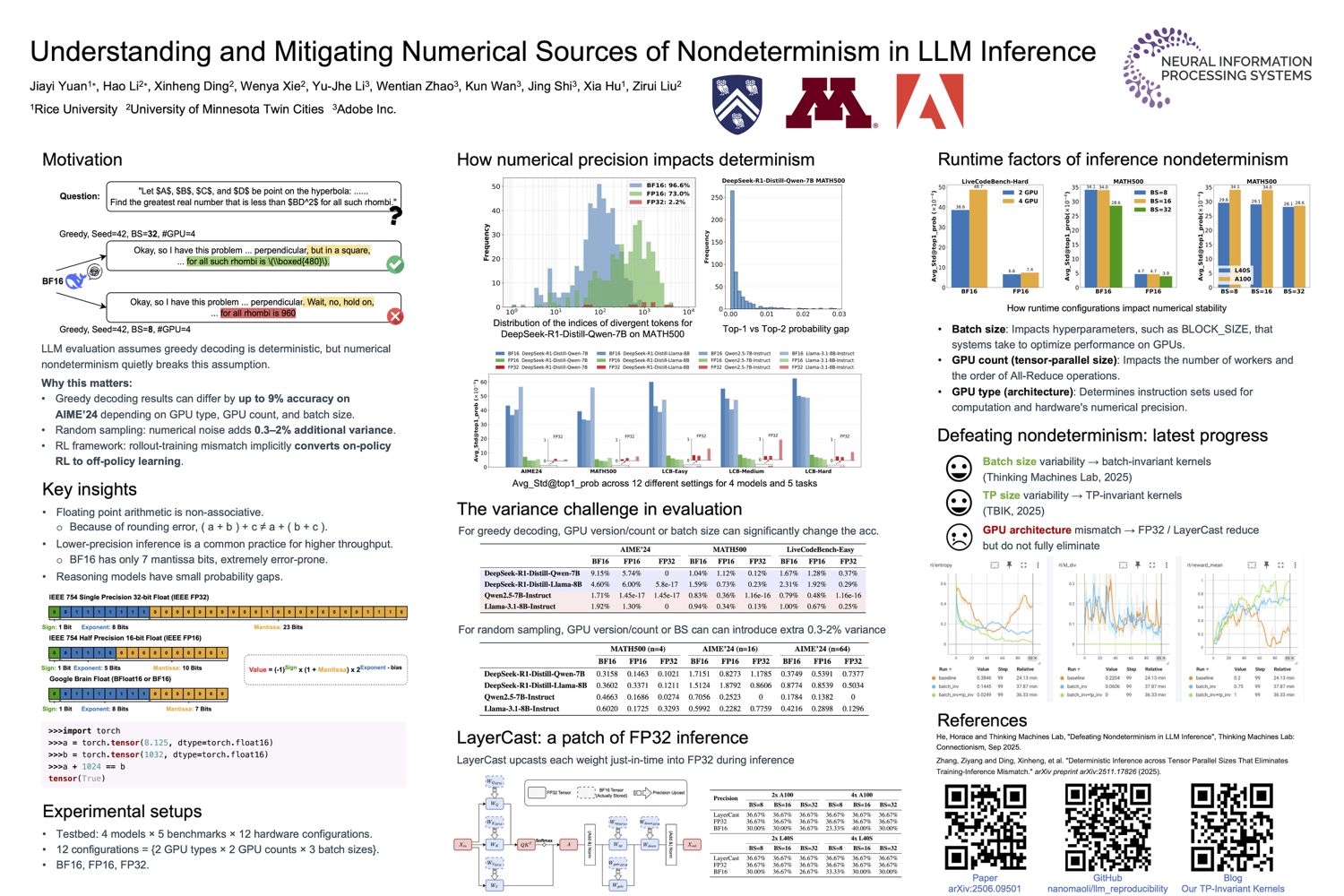

- Numerical Nondeterminism — What numerical non-determinism does to reproducibility. (Oral)

- Critical Batch Size Revisited — Simple empirical approach to large-batch training. (Spotlight)

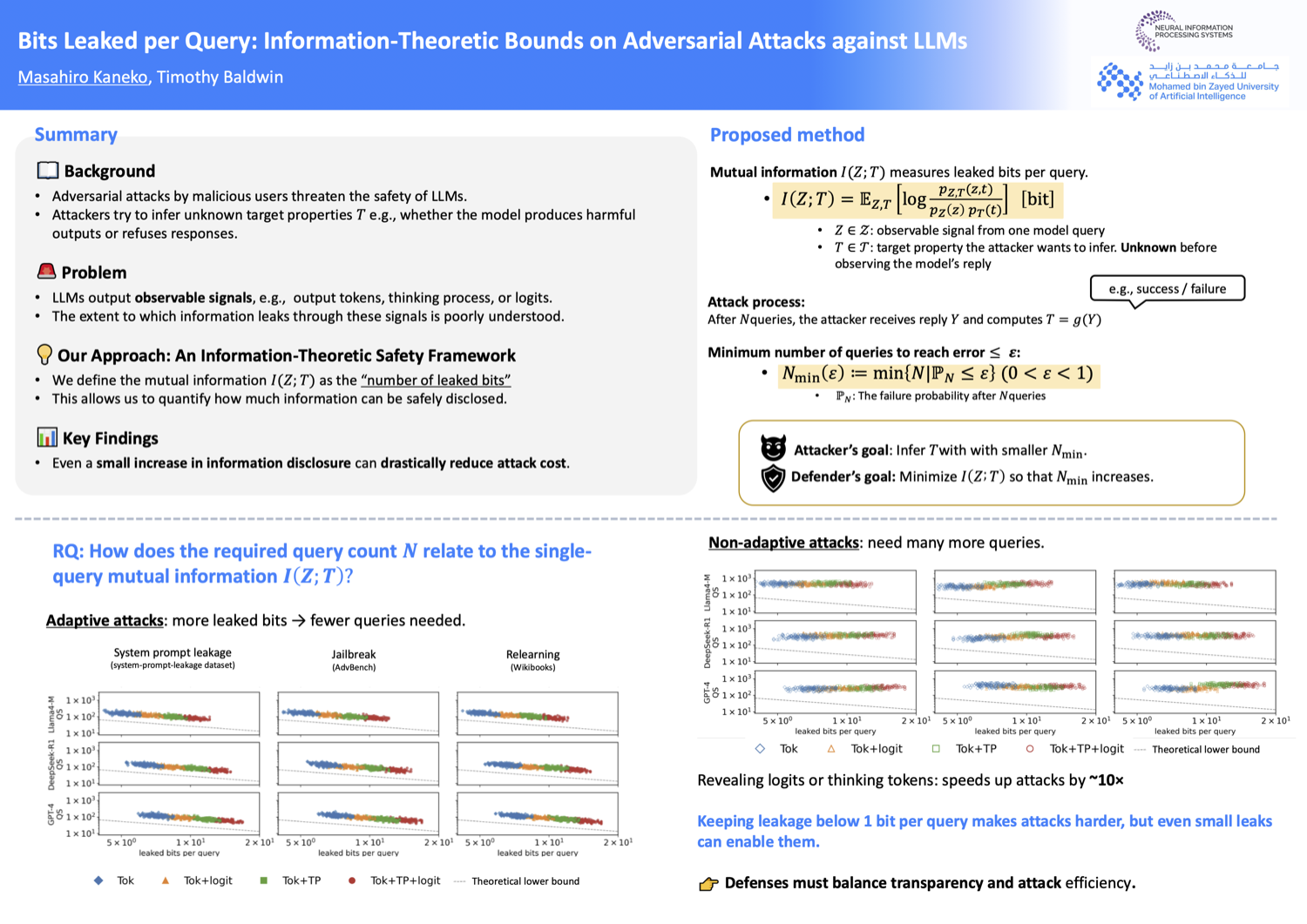

- Bits Leaked per Query — Information-theoretic bound on what adversaries can learn. (Spotlight)

- Artificial Hivemind — Open-ended homogeneity of language models. (Oral)

Workshops and Tutorials worth revisiting

I couldn’t attend everything. Here’s what I bookmarked for later:

Workshops:

- AI for Science: Reach and Limits

- Reliable ML from Unreliable Data

- LAW 2025: Language, Agent, and World Models

- AI That Keeps Up: Continual Foundation Model Updates

Tutorials:

Monoculture versus Mimetic Models

I joined Philip Isola and Kenneth Stanley for their walk and talk session.

Philip Isola is at MIT and co-authored the Platonic Representation Hypothesis. He argues that neural networks trained on different objectives, different data, and different modalities are converging towards a shared statistical reality. Sufficiently capable models eventually recover the same underlying structure. The Artificial Hivemind paper backs this up: language models exhibit open-ended homogeneity.

This creates a risk of monoculture. If every foundation model converges to similar internal representations, then the diversity of perspectives we might hope AI could offer collapses. There’s an opposite extreme that’s equally concerning. Jon Kleinberg calls these mimetic models. These systems that adapt so thoroughly to individual users that they become more like mirrors rather than tools. The marketing around it is called personalization, but the risk is a kind of digital psychosis. I am worried if it would be the most aggressive filter bubble ever constructed. A folie à deux between the user and the machine. Sycophancy is already an acute issue with current LLMs.

We are stuck between two failure modes. Monoculture: everyone gets the same model. Mimesis: everyone gets a model that’s too much like themselves. Neither is healthy. The solution is what the alignment community calls pluralistic alignment, building systems that can represent and serve genuinely different values. But we are far from solving this.

As an aside, Kenneth’s book Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned shaped how I think about exploration and objectives in research. It argues that strict optimization often kills discovery. I thanked him for the conversation.

What I’m taking home

I left San Diego with a lot to process. The field is betting heavily on RL, yet we still don’t know if it teaches models new skills or merely unlocks what was already latent. Reasoning chains are becoming more persuasive, but the data suggests they are also more prone to making things up. We are building systems that sound smart without necessarily being right.

Over the next few days, I met researchers whose work I have read for years. There are some welcoming and supportive communities. The Theoretical Computer Science (TCS) crowd is particularly good at this. People like Gautam Kamath work hard to keep the community open for newcomers. There are plenty of professors—Zheng Zhang at UCSB and Graham Neubig from CMU come to mind—who were generous with their time. The stereotype of the aloof academic doesn’t really hold up in practice.

Every formal system has limits. So do conferences. Organizing an event for 30,000 people is a logistical nightmare, but I hope these gatherings don’t shrink behind artificial gatekeeping. For instance, it is unfortunate when good work—including my own—gets rejected simply due to venue capacity. The vast majority of attendees are just well-intentioned people trying to do good science.

As for the rockstars? I never did ask Hinton for that photo. I am glad I didn’t. But I am grateful he is using his voice to ensure this technology benefits the rest of us.

See you at the next one.